the Correspondence of Hugo and Drouet

VIOLETA KERSZBERG & AGLAIA DEMENTEVA

A lock of Victor Hugo’s beard is preserved, sent in an envelope in 1873 to his lover Juliette Drouet.

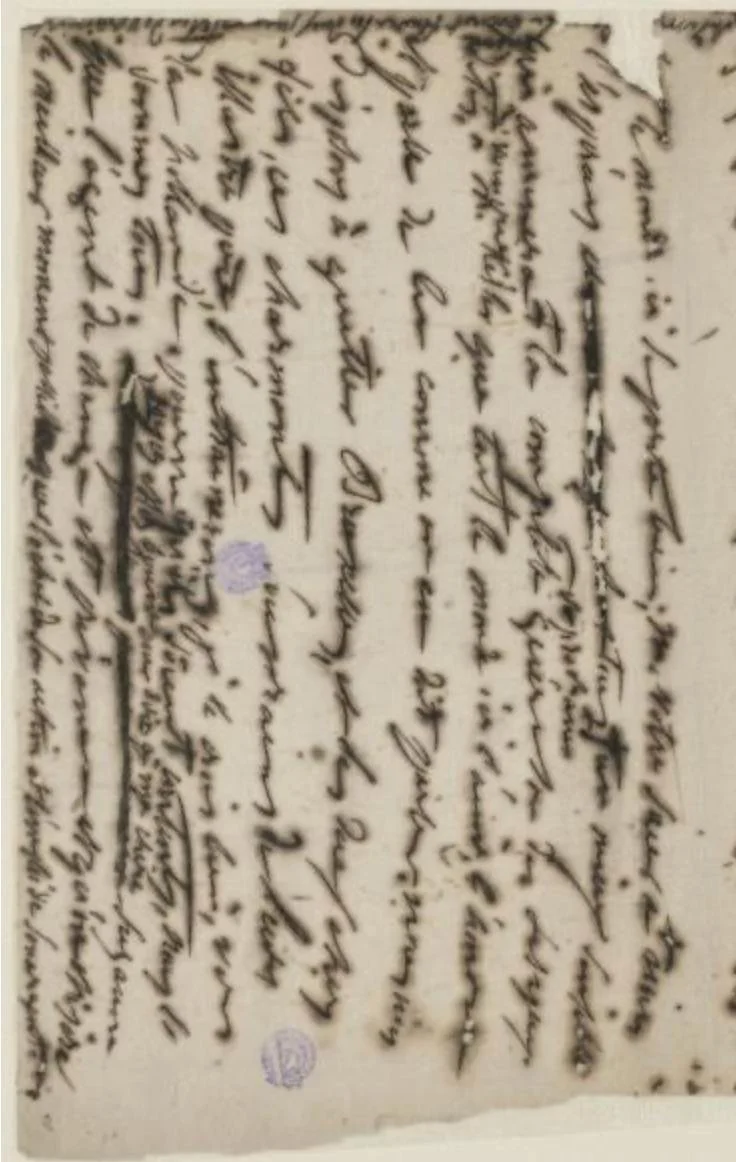

Before words, the more than eighteen thousand letters between Juliette Drouet and Victor Hugo were objects: papers with ink that had run, envelopes damp with tears, nervous strokes. Each one carried the mark of a gesture, and in their accumulation not only a story was recorded, but the attempt at a parallel body: an organism of paper and ink, folds and stains, raised in the image and likeness of the absent lover.

Victor Hugo’s beard, the locks of hair Juliette hid in the envelopes, and the ink stains do not speak only of writing, but of the urgency of giving language another flesh: the body that seeped between folds of paper.

In fifty years of correspondence, the lovers built a double that existed only on paper. A tactile echo of the other. The letters could be touched as foreign and dismantlable bodies. The challenge was to compose a presence, a fragmented body that was conjugated in the epistolary archive.

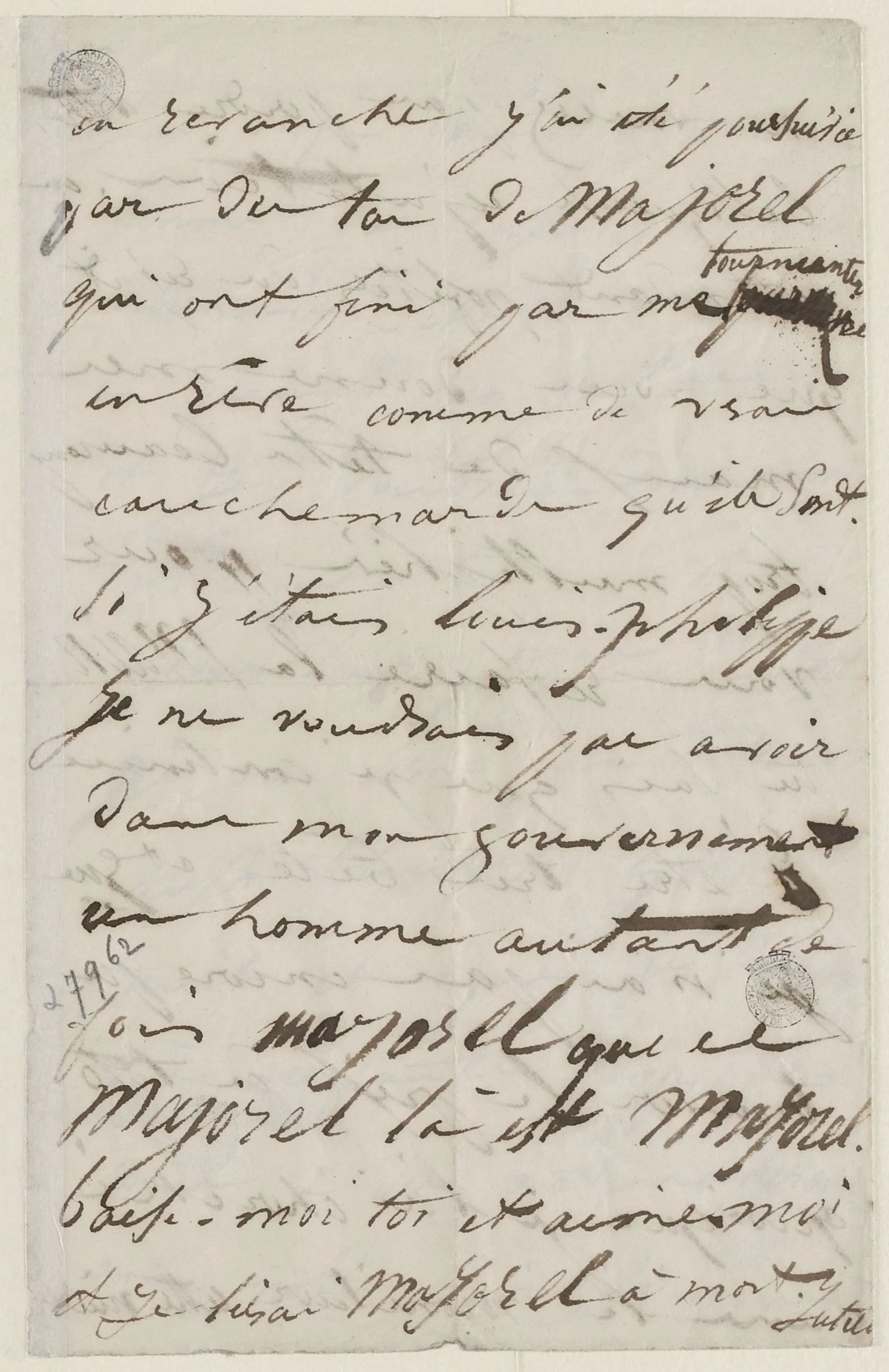

Barthes called it by another name, but he spoke of the same thing: of the lover’s attempt to fix desire in sensitive signs. A drawing, a lock, a stain of saliva were gestures that wanted to anchor the ungraspable on a concrete surface. What could not be touched on the other’s skin found its substitute in paper.

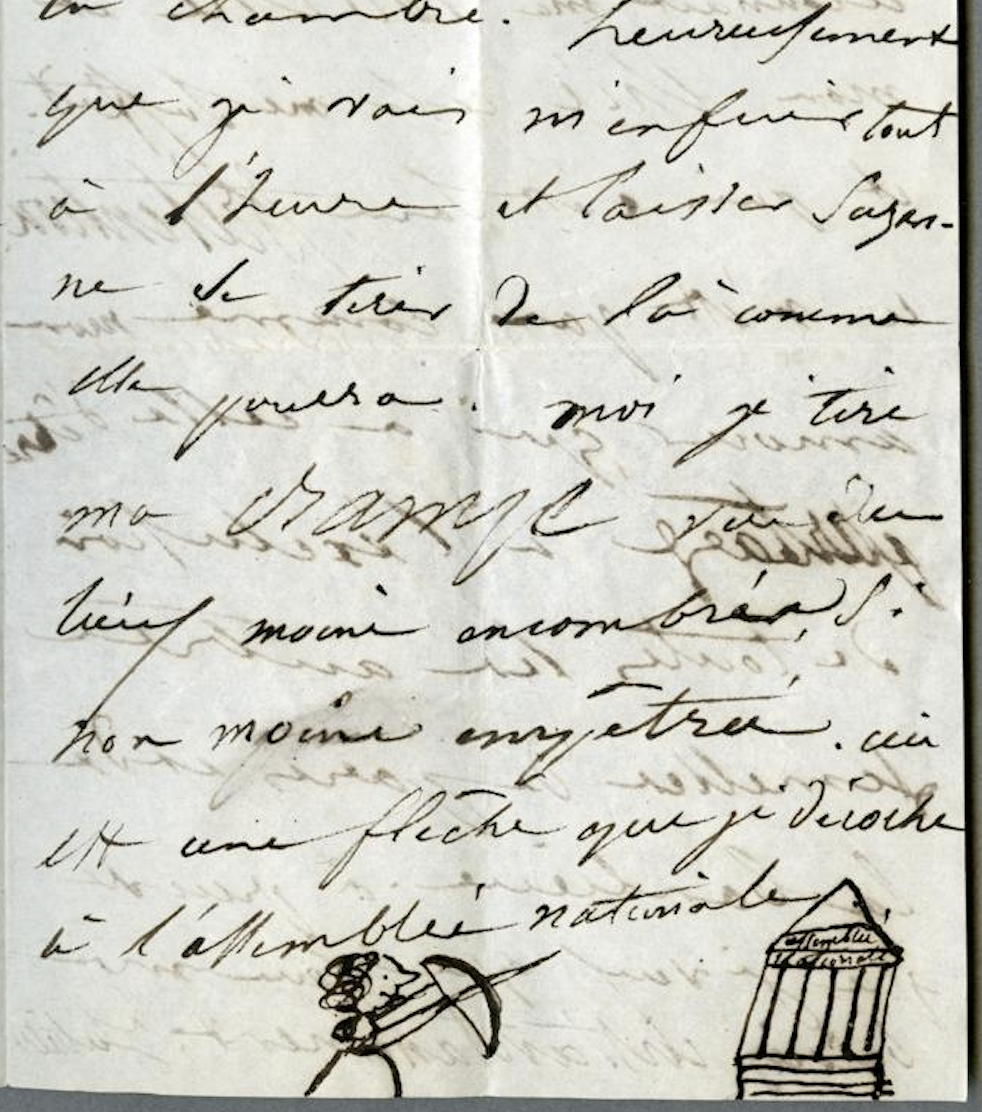

Juliette Drouet, besides being a prolific writer, filled her letters with illustrations and small caricatures. In a letter dated August 20, 1841, she drew Hugo with a pipe and red stockings. The ink of the drawing is not uniform: in the pipe there is a firm, decisive stroke, while in the face the line blurs and runs, as if Juliette’s hand had slipped a caress over the paper so that it would later impregnate the cheeks of her lover.

The correspondences between Juliette and Hugo do not trace a linear narration, but a vast and shifting archive of emotions. They are not static memories: the ink runs, the paper yellows, the folds wear out; and in that same process, memory is also transformed. Like skin, these materials record traces, scars, deterioration. Intimacy is not fixed once and for all: it becomes a living archive, open to be revisited.

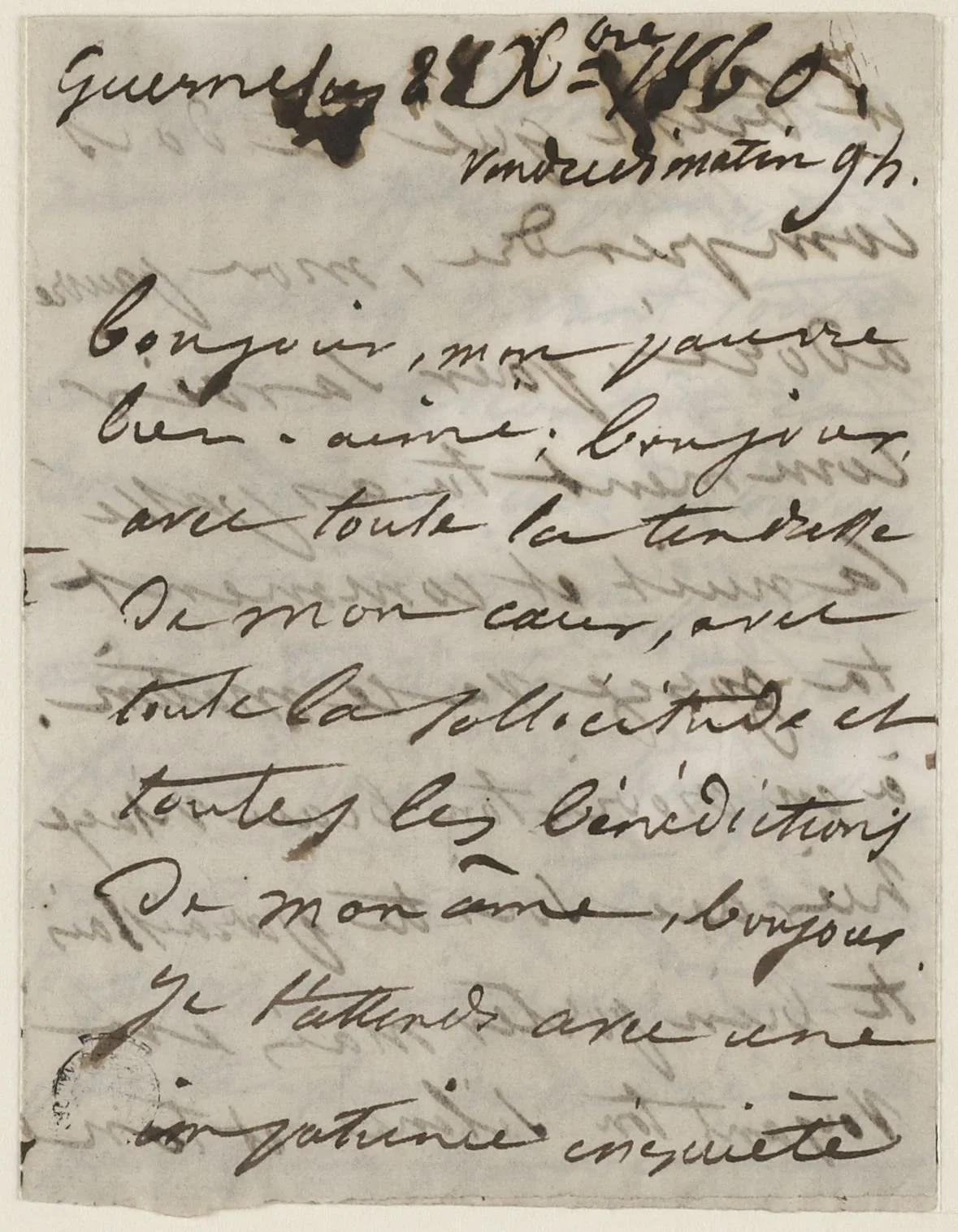

The epistolary courtship reveals another decisive figure of love: waiting. Juliette wrote much more often than Hugo replied, and each letter was an attempt to build a bridge in the middle of emptiness, to domesticate distance. Waiting was not a parenthesis between messages: it was the very stage of desire. Barthes imagined it as the theater of love, that suspended time where any sign of the other — a word, a stroke, an envelope — acquired disproportionate weight.

In that dilation, waiting is not passive, but a space where desire is cultivated and thickened, like an intimate laboratory in which the lover rehearses gestures to sustain the figure of the other.

The letters of Drouet and Hugo cannot be read only as testimony or historical document. They were, rather, a love experiment with the very matter of writing. Each envelope composed a third body: the letter-object. There mixed the ink that had run, the stamp torn off in haste, the lock of beard, the curl hidden between the pages, the dampness of the paper, the dust accumulated in the boxes, the erasures like scars. The correspondence forms its own ecosystem for encounter.

Perhaps, in truth, there is no love without objects. Perhaps desire always needs those third materials that sustain it. Bodies seek to survive in objects: not only to shorten distances, but to leave behind a living archive, a place where intimacy can transform and be reread by others.

Image by Luna Schapira